MAUSOLEUM

The Mausoleum

The word itself feels heavy in the mouth, like a stone dropped into still water: mausoleum. It comes from a single building, the original one, built around 353 BCE in Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, a satrap of the Persian Empire. His grieving widow-sister Artemisia II spared no expense. Greek architects Satyros and Pythius designed it, the sculptors Scopas, Leochares, Bryaxis, and Timotheus carved its friezes, and the result was so staggering that it instantly became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Fifty-some meters tall, it stood on a massive podium, ringed by thirty-six columns, crowned with a stepped pyramid, and topped by a four-horse chariot carrying marble portraits of the dead king and his queen. Earthquakes finally toppled it in the Middle Ages; crusaders later quarried its stones for their castle at Bodrum. Today you can still see a few battered reliefs in the British Museum and the broken greenstone foundation in Turkey, but the building that gave every grand tomb its generic name is itself a ghost.

Everything afterward is an echo.

There is the Taj Mahal, which is technically a mausoleum, though most people forget that beneath its perfect symmetry lies the actual reason it exists: Shah Jahan’s favorite wife Mumtaz Mahal, dead in childbirth, and later the Shah himself, shoved in off-center because his son locked him in a tower and took the throne.

There is Lenin’s Mausoleum on Red Square, squat and red-black, where a waxen corpse in a too-dark suit still lies under glass, periodically refreshed by a secretive team of embalmers who treat the body like a national battery that must never run down.

There is Grant’s Tomb in New York, a dour neoclassical box on the Hudson that nobody visits unless they’re on a school trip and even then mostly to ask “Who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb?” and laugh at the obvious answer.

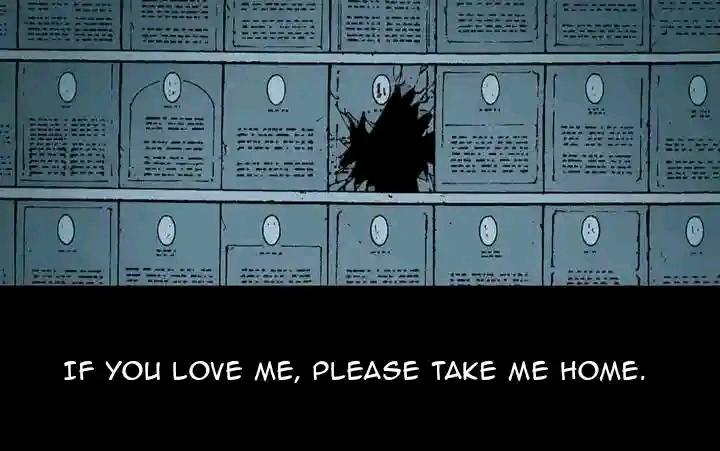

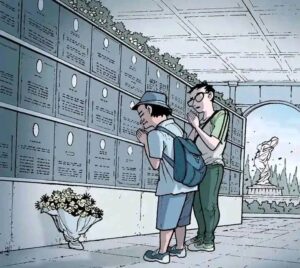

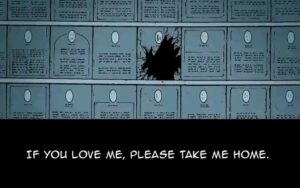

There is the humble mausoleum in your local cemetery: beige marble drawers stacked like post-office boxes, plastic flowers in metal vases, names and dates laser-etched so cleanly they look temporary.

All of them share the same stubborn idea: that architecture can out-argue oblivion. That if you pour enough marble, bronze, grief, and money into a sealed room, something of the dead will consent to stay. Sometimes the dead cooperate. Often they don’t. The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is rubble now, yet its name keeps getting reused, passed from tomb to tomb like a torch that refuses to go out even after the original flame is long dead.

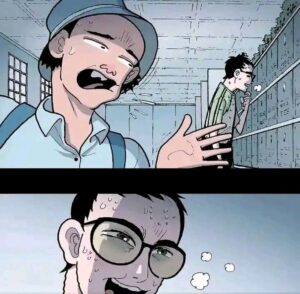

Stand inside any mausoleum at dusk, when the light slants low through narrow windows and the air smells of cold stone and carnations left too long. You will hear the faint echo of footsteps that aren’t yours, the soft click of a door that closed centuries ago. The building is doing its job: it remembers. Whether anyone living still does is another question entirely.